Terence Blanchard’s Met Opera Debut A Singular and Shared Success

Again and again in Fire shut up in my bones , Terence Blanchard’s magnetically powerful new opera, the emphasis returns to the tortuous weight of a burden carried alone. This weight, borne by the central character of the opera, stems from his sexual and emotional abuse in his childhood, and the resulting pain and alienation in his young adulthood. The struggle is singular and interior, but it takes place on a large scale against a hum of community, family and society.

This crucial relationship, between the individual and the collective, forms an irresistible meta-narrative for Fire shut up in my bones which has already made history as the first work by a black composer presented by the Metropolitan Opera. The public and company took advantage of the breakthrough in an emotional and memorable premiere at the Met on Monday night. And what was perhaps most remarkable about the performance was the clear and calm confidence with which Blanchard and his associates carried the weight of expectations.

The Met ordered Fire in 2019, after its well-received premiere at the Opéra Théâtre de Saint-Louis (which also presented Blanchard’s first opera, Champion ) . But the play was not intended as a season opener, let alone the first work to be presented after a long pandemic shutdown. Peter Gelb, chief executive of the Met, acknowledged that the Black Lives Matter movement, which intensified a conversation around performance last year, informed its decision to step up and prioritize this piece for the current season.

Blanchard, 59, is perhaps best known as a Grammy-winning multiple jazz trumpeter and conductor – his latest album, Absence, was released just over a month ago – but he has carved out an equally distinguished career in film music, not least through a long-standing association with Spike Lee. Opera is for him a recent field of activity, but also the continuation of a musical influence that he traced back to his father, a passionate amateur singer. And in Fire, he found a subject, a framework and an area of inquiry that could fully engage his vast musical imagination. He’s not the obvious choice to break the 138-year streak of opera by white Met composers, but as Monday’s triumphant performance showed, he was the right one.

Part of this correctness stems from Blanchard’s air of humility and inclination to see himself as part of a continuum. In a recent conversation for WBGO members during a break from rehearsals at the Met, he highlighted the community nature of this production. “One of the beautiful things about that for me is that it’s not mine,” he said, referring not only to co-directors James Robinson and Camille A. Brown, but also to librettist Kasi Lemmons and the rest of his creation. team – including the all-black cast. “And here’s the thing that I think makes the most powerful statement,” Blanchard added. “They all see themselves in these characters. You know what I mean? It’s the thing that really drives or directs the work that gets done.”

Fire shut up in my bones was adopted from a touching memoir by Charles M. Blow, which combines a coming-of-age story with a traumatic narrative, a search for personal identity, and an appreciation of the limits and possibilities of black masculinity. The main character of the opera is therefore Charles, embodied with brilliant gravity and charisma by baritone Will Liverman. A childhood version of Charles, known as Char’es-Baby, is played by the impressive young actor and singer Walter Russell III. Other wonders include Latonia Moore, imbuing Charles’ mother Billie with a vibrant emotional presence; and Angel Blue, who takes on three pivotal roles, including the personifications of a pair of intangible forces, Destiny and Loneliness.

Blanchard’s music for Fire is a vibrant consonant but full of subtle harmonic and timbral surprises (as well as strategic sparkles of dissonance). Composing for the cinema conditioned it to serve history, on stage or on the screen, without any vanity. And few orchestrators these days have such an organic understanding of crescendo and pulse, which Blanchard uses in opera to amplify emotional stakes, rather than plot mechanics. Often times, a change of chord color brightens up a state of mind, like in Act II’s tough moment when Loneliness comes forward as Charles’ one steadfast companion, truer even than family.

Surprisingly, given Blanchard’s profile as a jazz artist, Fire escapes description as a “jazz opera”. Its language is declared classic, with elements drawn from canonical composers, like Puccini, who defined Blanchard’s early exposure to the art form. But the smooth deployment of prolonged jazz harmony, often in breathtaking and fleeting passages, marks the piece as modern – as does the work of a rhythm section nestled within the orchestra, which in this production included Adam Rogers. on guitar, Matt Brewer on bass and Jeff “Tain” Watts on drums.

Working with Lemmons’ evocative libretto, which manages a shifting balance between outspokenness and poetry, Blanchard finds select passages in the text to add a vernacular touch. “African American singers in the opera world, when they come into this world, they are told to extinguish their heritage,” he told me. “Well, the thing we talked about at the very first rehearsal meeting, if you will, is that I want them to bring it all back into this.”

There is a point in Act I where Billie, describing the hardships of their rural Louisiana community, sings “They so so tiredness, “putting a pronounced blue undertone on“ tired. ”Later, her wayward husband, Spinner, seduces her with a promise of physical attention – and when he sings“ your tiredness, painful feet ”, his insistence on the word is a precise echo, in feeling and inflection. Elsewhere in the opera, Blanchard inserts touches of gospel vocality, and not only during a tragicomic play featuring a baptism from the South. “I bend, I don’t break, I balance,” Liverman sings at one point, filling the phrase with a heavy depth of feeling.

Form follows function throughout Blanchard’s work, and in Fire it finds musical resonance in a nourishing link with the natural world; in the rhythms of professional and family life; in the bluff, chatter between men and boys, especially Charles’s four older brothers. (“Why am I alone in a house full of noise?” He cries out, in one of Lemmons’ many lines that make you laugh even as they leave a trail.) The heart of the opera – the indecent assault on Charles an older cousin, Chester – is presented in absolute calm, with a quivering calm that amplifies its horror. A scene based on Charles’ later desire for comfort and affection (“Kiss me, love me, hug me, see me”) is associated with a 5/4 meter singing theme, in a perfectly romantic fashion that would sound at home in any of Blanchard’s film scores.

The vivid intensity of all this energy on stage – including Allen Moyer’s ingenious set design, a movable frame conveying minimalist rusticity – was received with exuberant rapture in the hall. A season opener at the Met is always a scintillating affair, at the intersection of high culture and high fashion. That night, a remarkable concentration of black excellence in the audience – Jon Batiste could be seen cuddling in the aisle during intermission, and I spotted pianist Jason Moran with his wife, the mezzo soprano Alicia Hall Moran – helped convey a distinctly different feeling. (Another contributing factor: the universal mask and the vaccination requirement that allowed for full capacity.) What might have looked under different circumstances like some sort of incursion recorded instead as a symbol of arrival: We here.

The Met has declared plans to incorporate more operas by black composers in the future – starting with the innovative Anthony Davis X, which will be staged in 2023 with Liverman in the title role of Malcolm X. That these changes are so long overdue was not made on Monday; they were happening, right now. Supreme assurance in all aspects of Fire, including the tactile specificity of its story, sharpened that feeling in the moment. All other considerations were swept to the periphery, where they remained just in sight.

The opera contains some notable dramatic deviations from Blow’s memoir. In an instant, Billie bursts into Spinner’s concert at a local juke joint, wielding a gun – a confrontation any jazz fan will associate with the tragic death of trumpeter Lee Morgan at the Slugs’ Saloon. (In his memoir, Blow describes his father as a former musician, not a worker, and although the gun confrontation took place, it was not at a club but at home.)

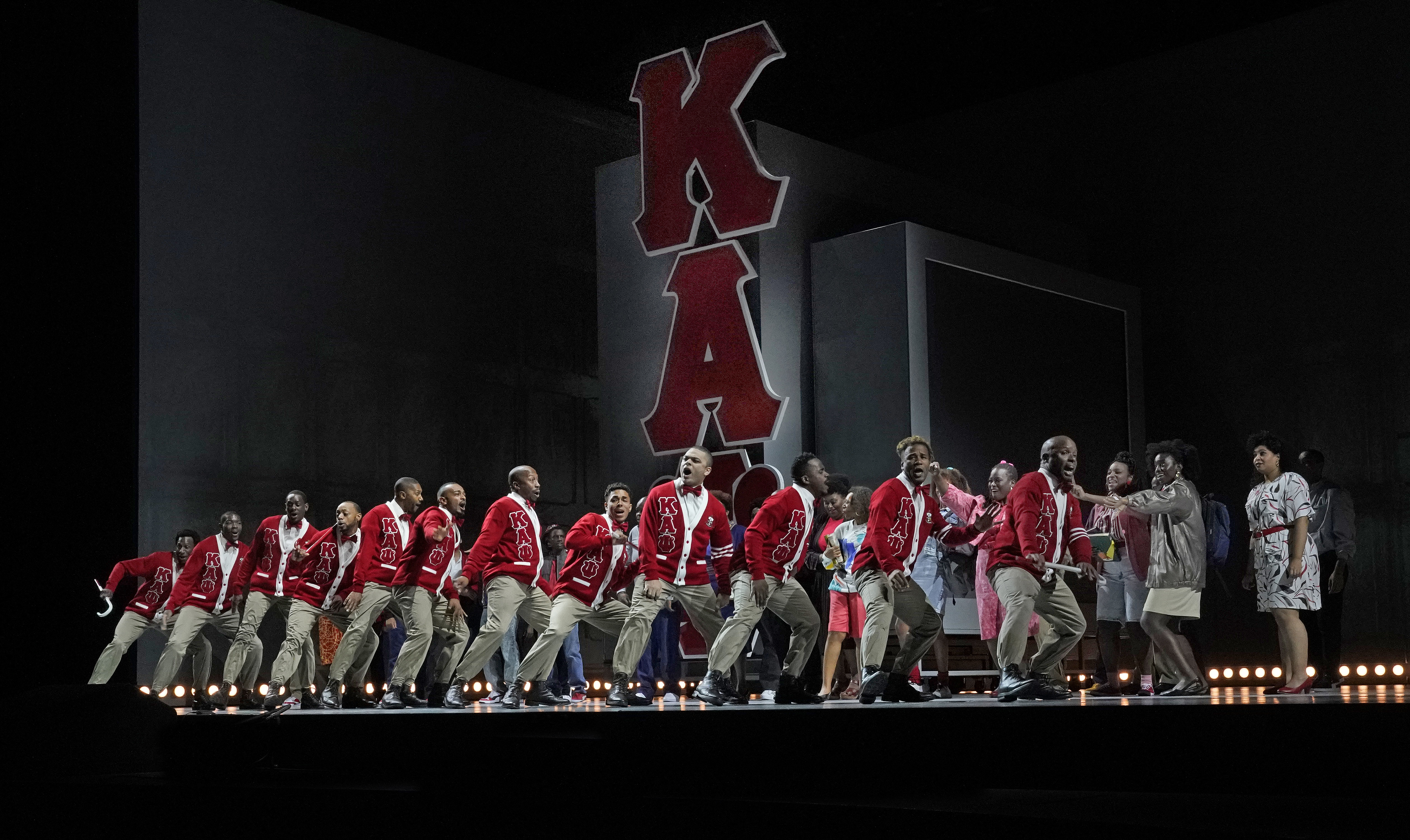

The juke joint play – like the gospel church service and a stage at the chicken processing plant where Billie works – lands with the deep force of authenticity, like a rare window into black life, at least one release. of it, in an opera setting. Act III opens with the noisy extravagance of a fraternal footstep routine, choreographed by Brown as a manifesto of irrepressible black joy. Just as it was worth marveling at what it meant for Beyoncé to bring the traditions of the HBCU marching band to the fashionable masses at Coachella, it was astounding to witness this jerk of proud Kinetic Blackness on stage. of the Metropolitan Opera. (Once the routine was over, the audience let out a sustained cacophony of applause.)

Blanchard was gracious in acknowledging that other black composers had long deserved the chance he was given on the opera’s biggest stage, and in his hope that it was not just a sign. But he and his associates also seized the opportunity, making Fire an undeniable declaration of their assertive presence. And it is particularly powerful that this historic work is not the fruit of a heroic tradition but rather of a journey of self-discovery and awakening. Charles learns that he doesn’t need to carry this burden alone, and that he never really has.

“This is not the end,” he swears, as the opera draws to a close. “Now my life begins.” As the company emerged for a series of boisterous recalls, joined by Blanchard, chef Yannick Nézet-Séguin and even a beaming Blow, it was impossible not to think about what was ending at that point and what could to start.